After coming back from the US and for my 2 last years in Kazakhstan I was really into long-distance running. I was training with a running/skiing club in the basement of one school (as my coaches couldn’t afford to rent a buidling so the basement was converted into a gym a.k.a. our little athletic heaven). The club was free to join and there were several age groups, 14-18 y.old folks and a younger group. There were around 25 of older us who were training consistently (and by that I mean twice a day every day apart from Sunday when we had a soccer/basketball game). We were one big family. The first training would start at 8am and last till 10, the second training of the day was at 4pm and could last till 7 or 8 as we would often stay longer and talk and just be together. My trainings’ count would be averaging at 50-55 per month and my gratitude back then (and now) for having found that club was immense. During summer holidays in 2012 we went on a camping trip to a place that was 150km away and some athletes from the club chose to cycle some parts of the road, some people chose to run (I was running as I didn’t have a bike). Of course, we took turns and rested in a van rented by our coaches, but that was already quite an empowering understanding – that you can leave your town on foot or by bike and head to another place kilometers away.

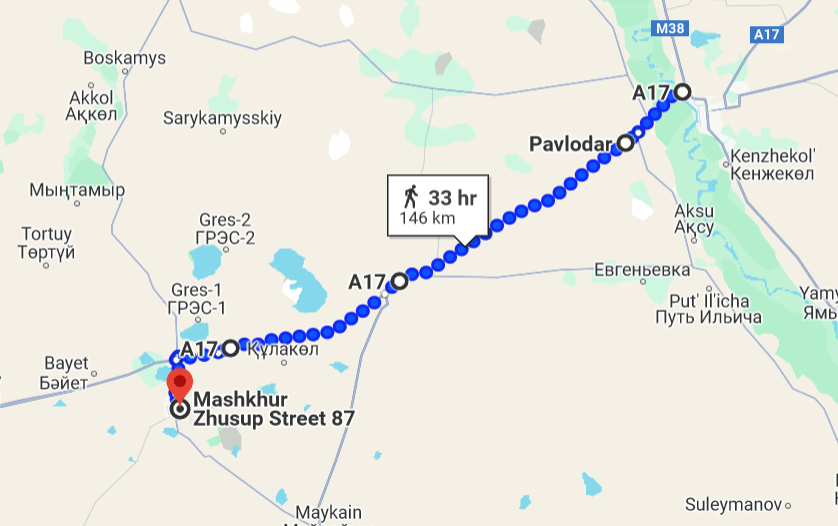

Next year, just before the high school graduation I have an idea of walking from my town to the town were the majority of my not-running friends lived at the time. The way would be really straightforward: cross the bridge across the river Irtysh, walk along the main (and the only) road following the signs, and eventually, after 140km+ arrive in Ekibastuz, a small mining town where a huge Gulag (nb. a forced labor camp for political prisoners/intelligentsia during soviet times) was located between the 1920s and 1950s and where a famous russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was imprisoned. Tbh, a big part of history of why so many russians (like me) ended up in these lands eventually is closely tied to political repressions of the soviet regime and forced relocations of people by Stalin and co. But this is another story which can be well consulted online.

Super-excited about this idea, I ask my friends Lina and Egor – who were originally from Ekibastuz – if they would like to join the walk. They were initially shocked, but then deemed it a great idea. They took a bus to my town with nothing but two little backpacks and a tent, and we set to leave at 3am from my apartment to greet the sunrise and to walk at least 15 hours as the plan was to complete the walk in 2 days for me to come back in time for my grad ceremony. There was not much to prepare: a tent, a headlamp, sleeping bags, several liters of water and some money to get food in villages on the way. We had recorded a video for our other friends who were laughing at us – in a good way – before leaving and went to sleep. At 3 am we woke up, my dad gave us a lift till the bridge across the river and we set off to walk A17 in the darkness.

You walk fast in the steppe. It is flat, there is no detour to make as there is not much to see. Just short yellow grass, some shrubs and blue sky. Monotonous and vast, just pick a pace (a good 6km/h is very easy to maintain in such conditions) and float through zen-ish landscapes. Day 1 was a day of understanding that walking along the road wasn’t the best idea, as the cars would stop and people would ask us how the hell we ended up there. We decided to leave the road and walk on the train tracks that were literally 500m away. It gave us a break from drivers, but at the same time gave us blisters from jumping on railway ties, and also the trains would sneak up on us and we would have to climb up and down the tracks to let the train pass. The day was hot, we ran out of water sooner than we thought, but the mood was great and we were joking and laughing. The first place where we stopped to eat and ask for water was at approx. km’50 and was just a шашлык-place off the side of the road. Our next hours were brightened by a box of ripe apricots found on the side of the road. Smiling at Universe’s gifts and snacking on juicy fruit, we carried on. The next place was a proper village named Kalkaman, where we realized we had walked 73 kms, that our feet were literally bleeding (thanks, blisters!) and that soon we would need to look for a place to sleep. At around km’80 and at approx. 9 pm we stumbled upon an abandoned salt mine a bit off the road, and decided to camp with a nice view of the mine below.

Day 2 started with a realization that we had walked 80 km in one day, and that our bodies were falling apart. Stepping back on A17 with the rising sun, we were joking that we “were full of energy and we would definitely reach the destination” though some nervous giggling had started to burst through. With all the eagerness to walk it all, at km’115 it was mutually decided that we would hitch a ride to move forward a bit faster. And we didn’t wait long. Some kind driver let us all in and in a dozen of minutes brought us to the entrance of Ekibastuz from where we walked to Lina’s house to sleep and heal our broken feet, backs and spirits. And oh boy, what a good decision it was! If we had walked all 140km I doubt I would have been able to show up the next day at the ceremony and wear high heels all day. 😁

I always remember these two days with the warmth in my heart, it was such an unusual endeavor, no glamour, no big aim. Just three people walking and laughing in the steppes.

In the next post.s I will tell about the eye-opening bike trip from Russia to Gibraltar that took place the following year. 🚴♀️🚴♀️

Have a good day,

Lots of love,

Lucy

Leave a comment